Updated December 26, 2025

In today’s connected healthcare environment, a medical device’s labeling is no longer just about operating instructions — it’s a critical cybersecurity safeguard. Without clear, complete, and accurate labeling, healthcare providers may unknowingly deploy devices with insecure settings, fail to apply necessary updates, or overlook known vulnerabilities.

The FDA’s 2025 guidance, Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions, makes this point clear: inadequate cybersecurity labeling can render a device misbranded under the FD&C Act (§502(f), §502(j)) and put patient safety at risk. For manufacturers, proper cybersecurity labeling is both a compliance requirement and a trust-building tool for hospitals, clinicians, and patients.

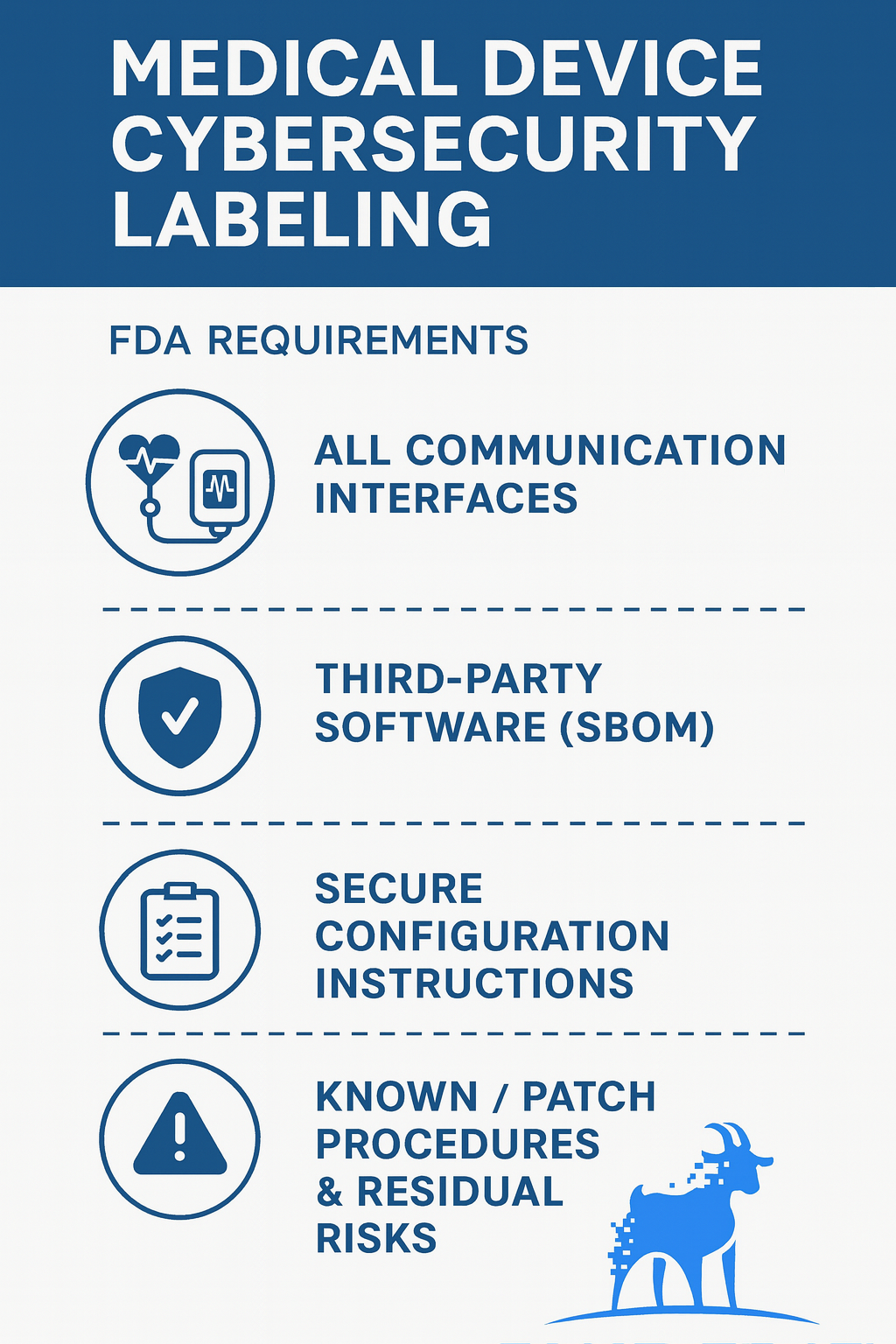

FDA Cybersecurity Labeling Requirements and What to Include

Section VI.A of the FDA’s Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions (2025) describes what the FDA expects manufacturers to communicate through cybersecurity labeling. In plain terms, your labeling should provide the intended users (e.g., hospital IT/security teams, HTM/biomed, and healthcare providers) with device-specific, actionable information they need to securely install, configure, operate, maintain, and decommission the device across its lifecycle.

FDA VI.A baseline: the core elements your labeling should cover

Below is a practical checklist you can use to align with the FDA’s labeling expectations while keeping the content usable for real-world deployment.

1) Communication interfaces and system exposure

Identify every wired and wireless interface, as well as logical interfaces, including those that are disabled by default or planned for future activation. Include:

- Physical interfaces (e.g., Ethernet, USB, serial)

- Wireless interfaces (e.g., Wi‑Fi, Bluetooth)

- Logical interfaces and services (e.g., APIs, cloud connections, remote service channels)

- Protocols/services used (e.g., TCP/IP, SNMP), and any required ports/services

Why it matters: Healthcare IT teams need to understand the device’s “attack surface” to plan segmentation, firewall rules, and monitoring.

Best-practice format: Add a simple “Interfaces & Services” table with columns like: Interface, Purpose, Protocol, Port(s), On by default (Y/N), Can be disabled (Y/N), Notes/constraints.

2) Third-party software components (SBOM-related summary)

Provide a labeling-level summary of key third-party components and versions (OS, libraries, frameworks, middleware), and indicate where authorized users can obtain the full SBOM. Include:

- Major third-party components and version identifiers

- A pointer to the complete SBOM location/process (portal, customer request workflow, etc.)

- Any constraints (e.g., “SBOM provided to authorized users under support agreement”)

Why it matters: When a new vulnerability/CVE hits a standard component, hospitals need to quickly determine whether they’re exposed and what to do next.

Tip: Keep labeling concise. Labeling can summarize “what’s important for users,” while the full SBOM remains the authoritative, detailed artifact.

3) Secure configuration and hardening instructions

Give step-by-step, device-specific instructions for secure deployment in the intended environment. Include:

- Authentication requirements (password policy, MFA expectations if supported)

- Authorization and user roles (e.g., RBAC setup, least privilege guidance)

- Certificate/key management expectations (where applicable)

- Network guidance (segmentation recommendations, allowed inbound/outbound flows)

- Which services/ports can be safely disabled

- Secure defaults vs. what must be changed on first use

Why it matters: Misconfiguration is one of the most common real-world causes of security issues. Clear instructions reduce both risk and support burden.

Best-practice format: A “Secure Setup Checklist” (numbered steps) plus an appendix/reference table (ports, protocols, firewall rules, required domains/endpoints, etc.).

4) Update and patch management procedures

Explain how users maintain device security over time—without relying on guesswork. Include:

- How updates are delivered (OTA, local media, vendor remote service, etc.)

- How authenticity/integrity is verified (e.g., digital signatures, secure boot checks)

- Expected downtime and any workflow planning considerations

- Failure handling and rollback steps (what to do if an update fails)

- Any user responsibilities vs. vendor responsibilities

Why it matters: Hospitals must maintain security while minimizing disruptions to clinical care. A clear update “runbook” prevents delays and unsafe workarounds.

5) Known vulnerabilities, residual risk, and compensating controls

If there are risks that cannot be fully mitigated without compromising clinical performance, disclose them clearly and provide practical mitigation strategies to address these risks. Include:

- A plain description of what remains and why

- The potential impact in user-relevant terms

- Compensating controls that the user can apply (segmentation, monitoring, access restrictions, configuration changes)

- Any operational constraints or “do not do this” warnings

Why it matters: Transparency enables users to manage risk responsibly and demonstrates a mature approach to risk communication.

Recommended additions that improve usability and reduce postmarket friction

The items below often make cybersecurity labeling far more helpful in practice—and can reduce review churn, customer confusion, and support escalations.

Logging and monitoring capabilities

Include:

- What security logs/events are available

- Log format and how to export/forward (e.g., SIEM integration options)

- Retention duration and any storage limits

- Time synchronization requirements (NTP guidance)

Why it matters: Without logs, hospitals can’t investigate incidents or meet internal security policies.

End-of-support and secure decommissioning guidance

Include:

- End-of-support policy basics (where users find current status)

- Secure retirement steps (data deletion, account removal, key/cert handling)

- Disposal/sanitization expectations where applicable

Why it matters: Lifecycle security includes “safe offboarding,” not just secure deployment.

Treat cybersecurity labeling as a living artifact

Plan to update labeling when:

- New vulnerabilities affect included components

- Update mechanisms or supported configurations change

- Older protocols/OS/platforms are deprecated

- Your recommended secure configuration evolves based on field learnings

This “living document” approach helps keep users secure and demonstrates ongoing cybersecurity maturity across the total product lifecycle.

How to Write Cybersecurity Labeling Hospitals Can Actually Use

Cybersecurity labeling should be written for individuals who deploy and maintain devices in real clinical environments, including hospital IT/security teams, HTM/biomed personnel, and service personnel. To make labeling usable (and defensible), focus on clarity and specificity:

- Write in tasks, not generalities: “Configure TLS 1.2+” beats “use secure protocols.”

- Define minimum secure settings: password length/complexity, MFA expectations (if supported), encryption standards, and segmentation guidance.

- Use quick-reference formats: tables for ports/protocols, firewall rules, required endpoints/domains, and a secure setup checklist.

- Include a simple network diagram: trust boundaries and data flows help teams deploy securely.

- Keep it consistent with SPDF/QMS artifacts: labeling should align with your threat model, risk controls, SBOM, and update strategy.

Common Cybersecurity Labeling Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

- Mistake: Documenting only “active today” interfaces

Fix: Include disabled-by-default and future-enabled interfaces to avoid surprises in the field. - Mistake: Hiding third-party and cloud dependencies

Fix: Provide an SBOM summary and clearly state where the full SBOM can be obtained. - Mistake: Vague hardening guidance

Fix: Provide step-by-step secure configuration instructions and minimum requirements. - Mistake: Unclear update/patch behavior

Fix: Explain delivery method, integrity checks, downtime expectations, and rollback steps. - Mistake: No residual-risk disclosure

Fix: Communicate known issues and compensating controls in user-relevant language. - Mistake: Labeling drifts from SPDF evidence

Fix: Ensure the story aligns with what you submit to the FDA and what you provide to customers.

Wrap-Up: Turn Labeling Into a Deployment Asset

FDA cybersecurity labeling is more than a submission requirement—it’s the operational guide customers use to deploy, maintain, and retire devices securely. The strongest labeling is device-specific, actionable, aligned to your SPDF, and kept current as vulnerabilities, configurations, and support policies evolve.

Key takeaways:

- Document all interfaces and exposure.

- Provide an SBOM summary and access path to the full SBOM.

- Give step-by-step secure configuration guidance.

- Make patching predictable (including rollback).

- Be transparent about residual risk and compensating controls

How Blue Goat Cyber Helps

At Blue Goat Cyber, we specialize in guiding medical device manufacturers through FDA-compliant cybersecurity labeling, from initial design through post-market updates. We combine deep regulatory expertise with real-world security engineering to ensure your labeling meets or exceeds FDA requirements, protects patient safety and data integrity, and supports your market access and reputation.

To ensure your device labeling is accurate, compliant, and trusted by healthcare providers, contact us today to schedule a consultation.

FDA Medical Device Cybersecurity Labeling FAQs

FDA generally expects device-specific, actionable instructions that help intended users install, configure, operate, maintain, and decommission the device securely. That typically includes: interfaces/exposure, SBOM-related component transparency, secure configuration guidance, update/patch procedures, and residual risk/compensating controls.

According to the FDA’s 2025 guidance, cybersecurity labeling should include:

- All communication interfaces (wired, wireless, cloud, APIs)

- Third-party software components and versions (SBOM summary)

- Secure configuration instructions for integration into the intended environment

- Update and patch procedures, including verification methods

- Known, unmitigated vulnerabilities with mitigation guidance

Not usually. A strong approach is to include an SBOM-level summary (key third-party components and version identifiers) along with a clear method for customers/authorized users to obtain the full SBOM (e.g., portal, support request process, customer package). The goal is to conduct a fast vulnerability impact assessment—without overwhelming the IFU with pages of component detail.

Yes. Labeling should reflect the true potential attack surface, including interfaces that are present but disabled, conditionally enabled, or planned for activation via configuration or updates. This prevents surprises for hospital IT teams and avoids credibility issues during review.

The FDA has established additional requirements for a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) for medical devices. In addition to the minimum elements defined by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), the FDA mandates including specific information. These additional elements encompass the support level, support end date, and known security vulnerabilities of the software components used in the medical devices.

While open source projects may not have designated support levels or support end dates, these additional elements largely apply to third-party or commercial components integrated within the medical device application. It is crucial to include complete and accurate SBOMs for medical devices, as they enable transparency and focus on cybersecurity.

Spell out the update workflow in operational terms: how updates are delivered (OTA/USB/vendor service), how authenticity/integrity is verified (e.g., signatures/secure boot), expected downtime, who is responsible (user vs manufacturer), and what happens if an update fails (rollback/recovery steps). Hospitals care less about buzzwords and more about whether they can patch safely without disrupting care.

Treat labeling as a living artifact. Update it when:

- a vulnerability affects included components (new CVEs),

- supported configurations or secure defaults change,

- update mechanisms/procedures change,

- you deprecate protocols/platforms, or

- you revise end-of-support/decommissioning guidance.

A good practice is “event-driven updates” plus a periodic review cadence (e.g., quarterly or biannually).

The device manufacturer is responsible for maintaining accurate and up-to-date cybersecurity labeling throughout the product’s lifecycle. This includes updating the labeling when new vulnerabilities are discovered, when patches are released, or when there are changes to the device’s configuration or intended use environment.

Yes. The FDA warns that inadequate cybersecurity labeling can render a device misbranded under the FD&C Act (§502(f), §502(j)), which may result in enforcement actions. It can also lead to increased liability if a cybersecurity incident causes patient harm due to missing or unclear instructions.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has established specific cybersecurity requirements that medical device manufacturers must meet. These include:

Secure Product Development Lifecycle: Manufacturers are required to implement a secure product development lifecycle. This involves reducing the number and severity of vulnerabilities throughout the entire lifecycle of their devices, from design and development to distribution, deployment, and maintenance.

Threat Modeling and Post-Market Vulnerability Management: Manufacturers must conduct threat modeling and outline plans for addressing post-market vulnerabilities. This includes patching and software updates to respond to potential security issues.

Coordinated Disclosure of Exploits and Software Bill of Materials: Details of the methods for coordinated disclosure of exploits must be included. Manufacturers must also supply a software bill of materials (SBOM) that details all third-party commercial, open-source, and off-the-shelf software components used in their devices.

Process and Procedures for Postmarket Updates and Patches: Companies must provide details on the processes and procedures for releasing postmarket updates and patches that address security issues. This includes regular updates and out-of-band patches for critical vulnerabilities.

These requirements apply to "cyber devices," which are defined as any devices that run software, have the ability to connect to the internet, and could be vulnerable to cyber threats. As of October 1, 2023, the FDA's refuse-to-accept policy comes into force for pre-market submissions that lack the required cybersecurity information.

Medical device manufacturers should familiarize themselves with the FDA's updated guidance document, "Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions," to ensure their products meet the required cybersecurity standards. Failure to meet these requirements could result in the FDA rejecting pre-market submissions.

According to the recent announcement by the FDA, medical device manufacturers are now required to adhere to a new policy related to cybersecurity. Under this policy, all new applicants for medical devices must submit a comprehensive plan that outlines how they will actively monitor, identify, and address potential cybersecurity issues. This plan should also include steps to ensure that the device in question is adequately protected.

Additionally, the FDA now mandates that applicants establish a reliable process that reasonably assures the device's security. This includes taking necessary measures to make security updates and patches available regularly and in critical situations. The applicants must also provide the FDA with a detailed software bill of materials, encompassing any open-source or other software utilized in their devices.

Overall, this new policy enacted by the FDA emphasizes the importance of cybersecurity in medical devices and aims to ensure that manufacturers take appropriate measures to safeguard patient safety and protect against potential cyber threats.

March 29, 2023, marked a significant milestone as the FDA began enforcing cybersecurity requirements for medical devices, urging manufacturers to comply with a Cybersecurity Bill of Materials (CBOM). A crucial element of the CBOM is the inclusion of a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), which outlines the comprehensive list of software and hardware components utilized within medical devices. This encompasses not only internally developed software but also third-party software and open-source components.

The significance of SBOMs lies in their ability to enhance transparency and accountability in the supply chain of medical devices. By mandating medical device manufacturers to self-attest to the accuracy of their SBOMs, regulators can obtain a holistic view of the components employed in the production of these devices. This promotes better assessment and management of potential security vulnerabilities.

One of the recognized standards for SBOMs is the Software Package Data Exchange (SPDX) format. SPDX provides a consistent and standardized way to document and share SBOMs, enabling efficient communication between various stakeholders, including manufacturers, regulators, healthcare providers, and consumers. This universal language supports interoperability and simplifies the evaluation of SBOMs by allowing for easy comparison and analysis.

The significance of SBOMs and SPDX in the present and future lies in their ability to fortify cybersecurity practices and enhance transparency across industries, not just within the medical field. As highlighted by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), the implementation of SBOMs should extend beyond medical devices, becoming a common practice in other sectors as well. This indicates a growing recognition of the importance of understanding and managing the software components in all connected systems.

With the regulatory enforcement of SBOMs, companies across industries are actively working towards creating compliant SBOMs, with some seeking assistance from third-party providers who specialize in generating accurate and robust SBOMs. These providers, like Synopsys, offer sophisticated tools and solutions that can precisely identify software components used, including third-party and commercial components. They can also ensure that the generated SBOMs align with the specific requirements set forth by regulatory bodies, such as the FDA.

Over the past few years, the Internet of Things (IoT), coupled with the ubiquitous nature of Information Technology, has resulted in an ever-expanding attack surface where rapid solution development and enhanced functionality routinely prevail over security. For example, attackers once disrupted most U.S. internet activity using 61 default IoT usernames and passwords. Consumers failed to change them before activating their devices, effectively turning our gadgets into culprits responsible for one of the largest Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) in the world’s history.

The healthcare industry is rapidly adopting IoT devices (often called the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)) to enhance patient safety and healthcare workers' treatment delivery. From medication administration to remote sensor monitoring, embedded medical devices are improving the quality of care and increasing interaction with their providers. While this technology was created with good intentions, the lack of security in product design phases is a major concern that will likely materialize into malicious action with grave consequences.

The consequences became clear in 2017 as researchers were able to acquire equipment (from $15 – $3,000) and intercept the radio frequencies from cardiac devices. With this capability, they could reprogram the devices to modify the patient’s heartbeat and drain the internal battery. As a result, the FDA recalled almost 500,000 pacemakers and enforced in-person firmware updates. Researchers have also demonstrated similar capabilities on infusion pumps and MRI systems.

Non-networked medical devices may be operating at a higher level of risk. Ease of access and the availability of RFID cloners contribute to a relatively weak physical security posture. In 2018, researchers demonstrated the capability to emulate and alter a patient’s vital signs in real-time using an electrocardiogram simulator they found on eBay for $100.

In late 2018, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General (IG) critiqued FDA procedures in assessing post-market cybersecurity risk to medical devices. To fortify the FDA's core mission “to ensure there is a reasonable assurance that medical devices legally marketed in the United States are safe and effective for their intended uses,” they outlined their ongoing efforts in enhancing medical device security.

According to the FDA, “Healthcare Delivery Organizations (HDOs) are responsible for implementing devices on their networks and may need to patch or change devices and/or supporting infrastructure to reduce security risks. Recognizing that changes require a risk assessment, the FDA recommends working closely with medical device manufacturers to communicate necessary changes.”

Blue Goat can help HDOs transfer that risk by evaluating the cybersecurity posture on your wired or wireless medical devices.

Contact us today and inquire about our full-range penetration testing.

We can significantly increase your patient’s safety while reducing your organization’s risk.

The lack of security in many medical devices can be attributed to several key factors. One significant factor is the increased scrutiny over the vulnerabilities of these devices, which ultimately forced regulatory bodies like the FDA to reassess their cybersecurity requirements. A report by the FBI revealed that a staggering 53% of digital medical devices and internet-connected products had critical vulnerabilities, exposing patients and medical providers to various security risks. These vulnerabilities were often found in unpatched and outdated devices, which served as the weak link in the cybersecurity chain. Moreover, research suggests that 88% of healthcare cyberattacks involved an IoMT (internet of medical things) device, further underscoring the urgent need for robust security measures.

Inadequate security controls in medical devices have long been a pressing issue. Many of these devices have been designed with a primary focus on their medical functions, with security measures being added as an afterthought, if at all. These "bolted on" security controls have proven to be less than adequate, leaving vulnerabilities that malicious actors can exploit. Additionally, the lack of mandatory requirements and accountability in the past has contributed to the lax approach towards security in the industry. However, recent changes have brought about a much-needed shift in mindset. Introducing new regulations and the potential for costly fines for non-compliance have made it clear that the days of overlooking security are over.

The consequences of cyberattacks on medical devices are grave and can have a significant impact on patient safety and healthcare institutions. Direct interference with device operations can lead to incorrect treatment, posing severe health risks to patients. These security breaches not only pose immediate dangers but also erode confidence in the reliability and safety of medical devices and healthcare institutions as a whole.

Recovering from a cyberattack can be a costly and time-consuming process. It often involves device recalls, software upgrades, and potential legal implications. These measures are necessary to address the vulnerabilities exploited during the attack and prevent further breaches in the future. Healthcare institutions must invest in robust cybersecurity measures to safeguard networked medical devices and protect patient health.

Moreover, the potential for cyber attackers to gain remote control of medical devices is a cause for concern. This unauthorized access allows them to manipulate device settings, administer incorrect doses of medication, or disrupt the vital functions of life-support machines. Such malicious actions can have life-threatening consequences for patients, underscoring the urgent need for enhanced cybersecurity measures.

It is imperative that the medical profession prioritizes the security and safety of networked medical devices. Steps must be taken to reduce the risk of cyberattacks, ensure the integrity of medical devices, and maintain patient trust in healthcare institutions. By promoting a proactive approach to cybersecurity, we can mitigate the potential harm caused by cyberattacks on medical devices and safeguard patient well-being.

Networked medical devices are interconnected devices used in healthcare settings that rely on wireless technologies. These devices play a crucial role in patient care, such as insulin pumps, pacemakers, infusion pumps, patient monitors, MRI machines, and more. They enable doctors and healthcare professionals to remotely monitor and manage patients, providing efficient and minimally invasive procedures.

However, the increasing interconnectedness of these devices has raised cybersecurity concerns that cannot be ignored. When networked medical devices are compromised, they become vulnerable to malicious attacks by hackers. This poses a significant risk to patient safety, potentially resulting in severe harm or even death. The urgent need for robust cybersecurity in healthcare technology is underscored by several high-profile instances of medical device hacking.

For instance, insulin pumps have been manipulated remotely, exposing patients to the risk of insulin overdose. Pacemakers, essential devices for regulating heart rhythms, have vulnerabilities that can be exploited by hackers to alter heart rhythms or deplete the battery, leading to life-threatening situations. The infamous WannaCry ransomware attack on the UK's National Health Service demonstrated how cyber-attacks on hospital networks can indirectly impact patient care and safety.

These vulnerabilities clearly highlight the critical importance of enhanced security protocols, regular software updates, and vigilant monitoring. By implementing these measures, healthcare providers can protect patient safety and ensure the reliability of these essential networked medical devices. It is imperative to address these cybersecurity concerns to maintain the trust and integrity of the healthcare industry while harnessing the benefits and advancements offered by interconnected medical devices.

Medical device software testing is a critical process aimed at ensuring that software embedded within or designed to control medical devices functions accurately, reliably, and in compliance with regulatory standards. This testing verifies the software's adherence to its intended functionality, user interface, integration, and overall performance requirements as dictated by medical device regulations, such as the FDA's 21 CFR Part 11 and the internationally recognized IEC 62304 standard. The objective is multifaceted, encompassing the removal of defects in software architecture and code, ensuring the software meets strict regulatory compliance, and ultimately contributing to the production of world-class, safe medical devices.

Key components of medical device software testing include:

Functional Testing: This evaluates the software's operational aspects to ensure it performs its intended functions correctly. It involves detailed testing of the software's features and capabilities.

Device Verification Testing: It verifies that the device as a whole, including its software, meets all specified requirements. This testing ensures that the product is designed correctly and works as expected.

Security Testing: Given the sensitivity of medical data and the potential impact of cybersecurity threats, testing for security vulnerabilities is essential. It helps in identifying and mitigating potential security risks.

Interoperability Testing: This ensures that the medical device can operate compatibly and safely with other systems or devices. It's crucial for devices that are part of a larger ecosystem of medical equipment.

Usability Testing: Focused on the human-device interaction, usability testing ensures that the device can be used efficiently, effectively, and satisfactorily by the intended users.

Performance Testing: This assesses the software's stability, speed, and scalability under various conditions. It is crucial for ensuring that the software can handle its intended workload without failure.

Compliance Testing: Ensures the software meets all relevant regulatory and industry standards, focusing on safety, quality, and reliability requirements specific to medical devices.

Medical device software testing follows a rigorous methodology that includes planning, requirement analysis, test case development, execution of tests, and thorough documentation throughout the testing cycle. This methodology is designed to identify and address any defects or anomalies in the software architecture, code, or performance before the device reaches the market, thereby ensuring the safety and efficacy of medical devices. The process involves a combination of automated and manual testing techniques and requires a deep understanding of both the technical and regulatory aspects of medical device development.

Common medical device vulnerabilities encompass a range of issues that can compromise the safety, privacy, and effectiveness of medical devices. These vulnerabilities are often related to software flaws, outdated operating systems, or insecure interfaces, which cyber attackers can exploit to gain unauthorized access, steal sensitive data, or disrupt device functionality. Some of the most prevalent vulnerabilities include:

- Insecure Network Connections: Many medical devices connect to healthcare networks via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth, making them susceptible to eavesdropping or unauthorized access if they are not properly secured.

- Outdated Software and Firmware: Devices running on outdated software or firmware are vulnerable to known exploits that have not been patched. This includes operating systems that are no longer supported by their vendors.

- Weak Authentication and Authorization Controls: Insufficient authentication mechanisms can allow unauthorized users to gain access to medical devices, potentially leading to misuse or the alteration of critical healthcare information.

- Lack of Encryption: Failure to encrypt sensitive data both at rest and in transit can expose patient health information (PHI) and other confidential data to interception and misuse.

- Third-Party Software Components: The use of vulnerable third-party software components can introduce additional risks, as device manufacturers may not always regularly update or patched these components.

- Configuration and Customization Errors: Improper configuration or customization of medical devices can leave them open to attacks. This includes default passwords never changed or security features that are disabled for convenience.

- Physical Security: Physical access to medical devices can also pose a threat, especially if devices are not adequately secured within the healthcare facility, allowing for tampering or theft.

Addressing these vulnerabilities requires a comprehensive cybersecurity strategy that includes regular software updates and patches, strong encryption methods, robust authentication and authorization controls, and vigilant monitoring of network connections. Additionally, collaboration between device manufacturers, healthcare providers, and cybersecurity professionals is essential to ensure the ongoing protection of medical devices against emerging threats.